A Fluid Borderland

The Mediterranean is often depicted as a fluid space: a region that is constantly reinvented through the re-enactment of its territorial borders and the silencing of its migrant voices.

This process has not started yesterday. But it involves a long history of systematic expulsions, of discriminations, of imposed inferiority and of alienation. But the Mediterranean is, above all also, a space of desire; it remains caught between the poetic articulation of a shifting, cultural formation, and the the trauma of a returning middle passage, a space of connection that integrates the area’s cultural roots within the routes of its constant displacement.

This geography has a particular time and space. It expresses itself through specific interconnections: small, mobile settlements interact with the constantly fluctuating sands of a cyclical extraction: from the oil fields of the Viggiano mountains to the plains around Venosa and Cerignola, where an intensive industrial agriculture has taken the place of local subsistence economies, to the new opportunities of renewable energy exploitation…

… and everywhere the thickness of black heavy earth, evaporating in the morning sun.

In Basilicata, a region in the Central South of Italy, more than 250 thousand people emigrated from the region between 1869 and 1912, mainly to Northern Italy, Europe and the Americas. This desertification has only intensified over the last decade –leading to a rapid depopulation. The exodus remains especially important among the young and highly educated, most of whom will never return to Basilicata once they end secondary school.

More than in other regions of the Central Mediterranean, the emigration from Basilicata represents a phenomenon that changes its outlook and deprives it of its force. Already at the end of the 19th century, a parlementary enquiry noted that mass emigration from this region principally involved economic and social causes. At the end of the second World War, Basilicata continued to demonstrate an extreme inequality in land ownership. An agricultural reform programme during the 1950s and 60s tried to face these inequalities by redistributing some of the extensive land holdings or latifondi.

But the resumption of the exodus during the 1960s and 70s demonstrates the undoubted failure of this agrarian reform. The main causes are the inefficiency of agricultural property redistribution, erroneous policies of industrialization and the strengthening of clientelism in public offices -which rapidly contributed to a system of “wealth without development”1

1. Alessandro D’Alessandro, Aggravata nel ventennio ‘51-’71 la situazione della Basilicata, “Basilicata”, XVIII, 1 (1974), pp. 47-49

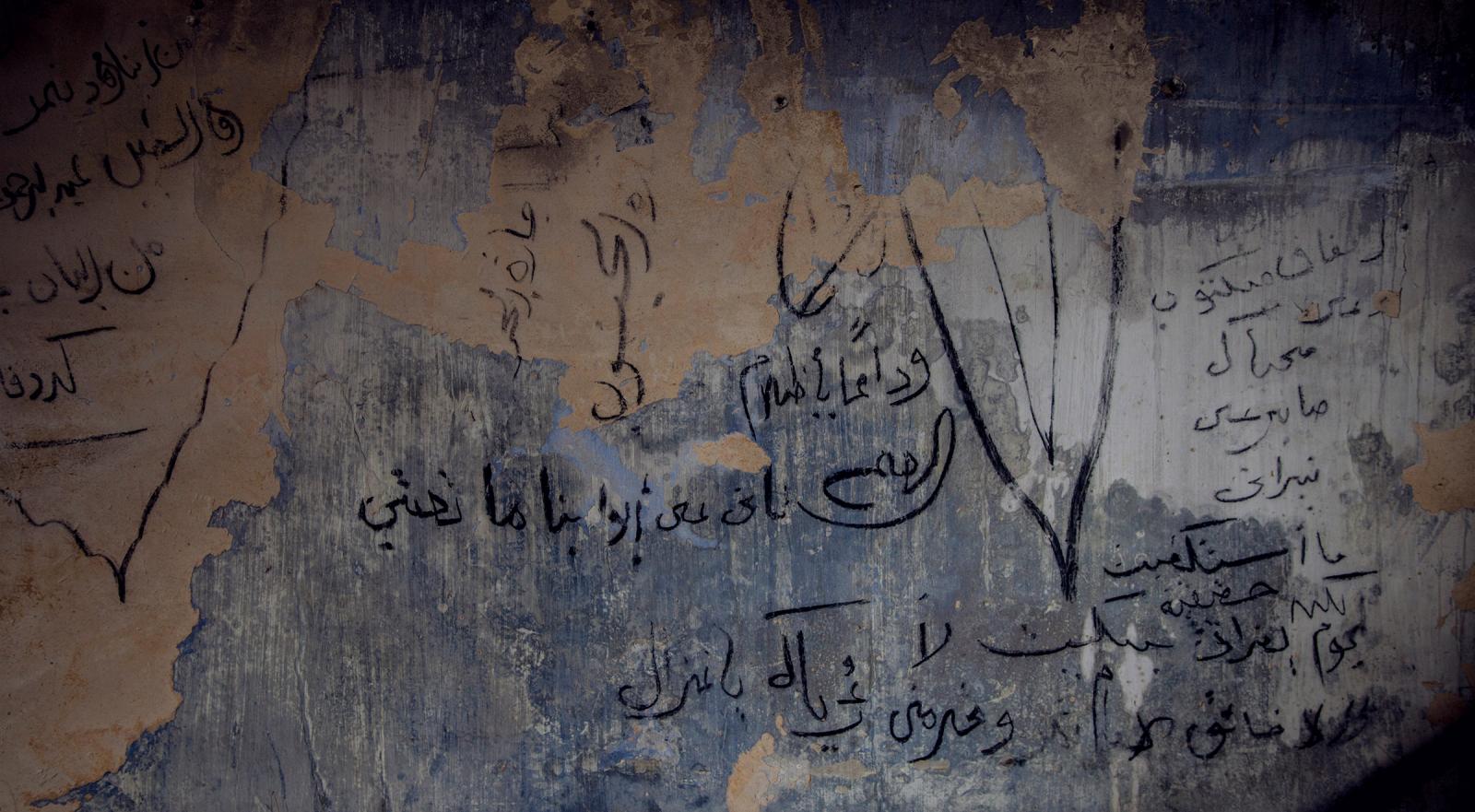

Gennaro Mennuti, the mayor of Montemilone, a town of 1200 permanent inhabitants. His two daughters have gone away to find work… “and I know they will never come back”.

Yet while the partial agricultural reform has enabled state institutions to partially reclaim this vast territory, it also produced devastating effects.

On the one hand, it enabled the new owners of the land to freely buy and sell their properties with the support of credit institutions. These measures were specifically set up to overcome the territory’s presumed ‘backwardness’, promote development, and put pressure on the agricultural labourers to regain the land.

On the other hand, this privatization also partly deepened the gap between what the Italian sociologist Piero Bevilacqua calls the polpa (flesh) and the osso (bone) of the Italian peninsula. Between the irrigated lowlands around the Ofantino river (the Piana) and the hills and mountains of the Alto Bradano (i monti) a vast gap appears, which separates farming communities and their kin.

Mayor Altobello explains: “In the vicinity of the river, the systematic irrigation of our fields has enabled a booming agriculture… We note a progressive diversification of agricultural production in this zone, between zootecnical enterprises and, above all, horticulture. This sector covers over 400 ha nowadays. It comprises 40-50 agricultural enterprises, which mostly produce for the big distribution networks –supermarkets located in Northern Europe. [As a result] we require a working force all year round.”

Towards the hills a more extensive agriculture prevails, however. In contrast to the Piana, agricultural enterprises are much smaller here. Most enterprises do not own the land they work on. And farming enterprises only have access to private wells –some of which are located at more than 150 meters in depth.

As one local farmer explains: “If you consider an average farm of 10-15 hectares, you need to work with a five-year rotation. This means you have to constantly find irrigable land for rent, which is not at all easy. One clear indicator for increasing property concentration around here is the corporate surface, which is constantly on the rise… So with pressures rising, and the EU subsidy framework making lots of demands, small farming enterprises here are confronted with little liquidity, also because they must balance rising costs.”

Hillside agriculture is characterized by monocropping. Over the past three decades, monocrops have shifted from tobacco, to sugar beets to tomatoes.

In order to gain a minimum wage from European subsidies, farmers are forced to move deeper and deeper into unexplored terrains. Some have started to reclaim degraded grasslands for agriculture, principally for the cultivation of durum wheat, thus generating more soil erosion as well as new challenges to community resilience.

If the current trend continues, in the next twenty years, Basilicata will basically become a desert. Exponential drought and intense precipitation patterns already produce advancing landslides and erosions. Working at the mercy of global markets, farmers have little say over the price or the goods they produce. And communities continue to suffer from mass emigration and lack of local opportunities.

But the Mediterranean is not all destruction. The countryside on the boundary between Puglia and Basilicata in particular has also become an environment of intense movements and interconnections.

Since the mid-1980s, groups of migrants have started to arrive here, either transitorily or to settle permanently. In the towns and villages that have been emptying since decades, the number of inhabitants rarely reaches over 5000. Here, new generations of migrant workers have started to fill the ranks of emigrated farm workers and day labourers – actively contributing to local development.

Public infrastructures like schools and hospitals survive thanks to the presence of these immigrant communities. From 2002 to 2010 the number of foreign residents in the region has quadrupled (+ 13.4% only in the last year of that period).

Generally speaking, migrant labourers comprise almost one third of the total agricultural labour force in the country: in 2017, out of about one million agricultural workers, 286.940 were estimated to be migrant workers, according to the national labour syndicate FLAI-CGIL.

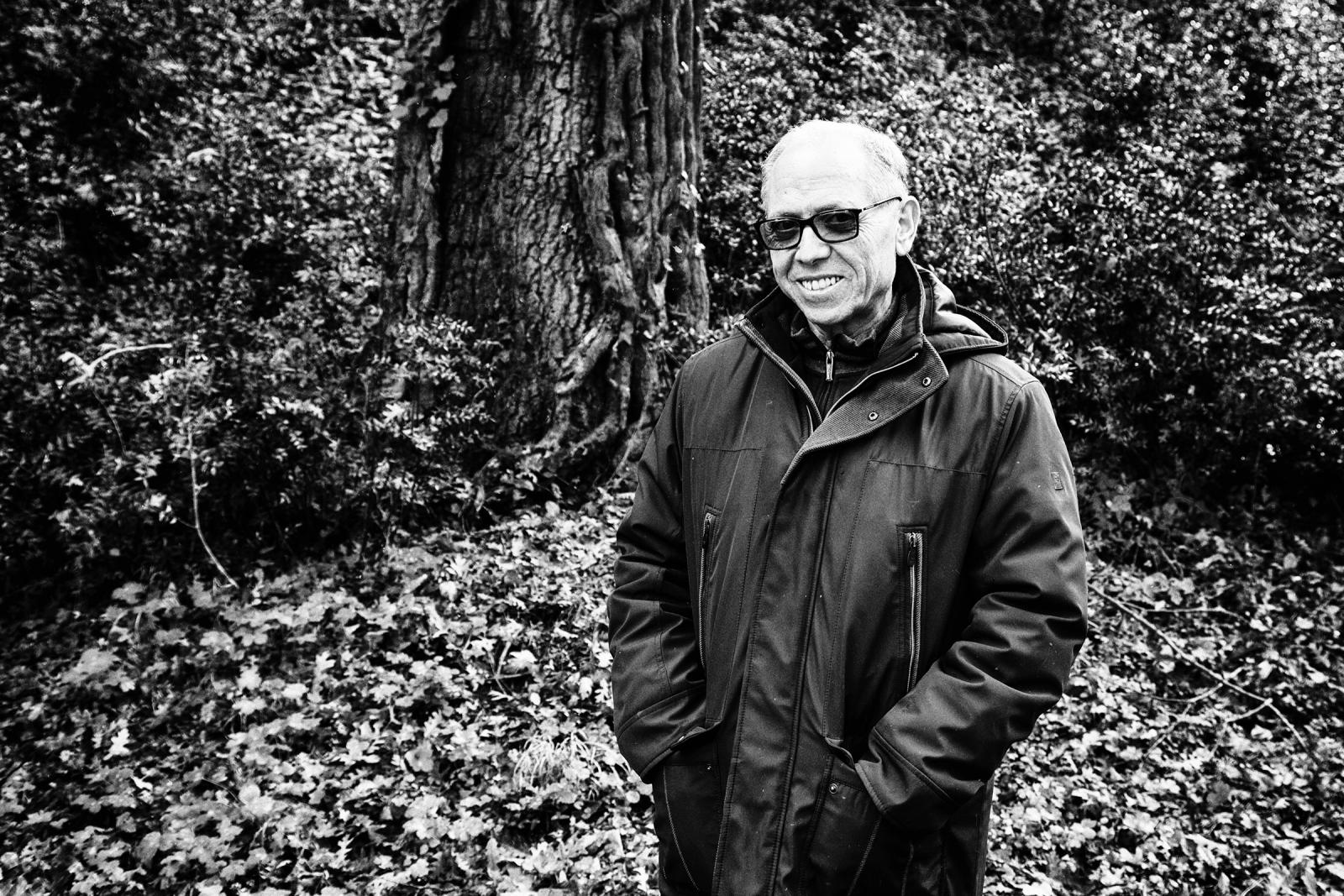

The settlement of migrant workers usually follows a common pattern. Whenever a new crop is introduced, groups of workers settle temporarily on cultivated lands: occupying the ‘ruins’ of abandoned houses, warehouses and derelict buildings left over the from destitute agricultural reform. Most foreign residents in Basilicata come from Eastern Europe and from Subsahara Africa. Especially the latter has been affected by a similar exodus since the eruption of civil war in Libya, which has forced many Africans to travel to Europe.

The interaction of immigrant workers with local residents and political institutions raises a series of important questions: first, what are the longer term implications, in political and cultural terms, of this intermittent but increasingly permanent presence of immigrants on Southern European soils? Secondly, how are these immigrant settlers challenging and transforming existing equilibria in terms of capital-labour relations, politics and urbanization? And finally, how are these constant interactions transforming ‘local’ identities?

One area where this tension has become particularly apparent has been the production of industrial tomatoes. Around 1990s, this new crop was introduced in the heart of the prior agricultural reform area. Ever since it has rapidly upset existing equilibria.

The expansion of the agricultural frontier always unfolds in the same manner. Similarly to the Piana, groups of workers, originally from Tunisia and Morocco, started to temporarily settle in the abandoned ‘ruins’ around Irsina.

Once the new crop is introduced, local entrepreneurs launch a demand for flexible labourers to plant, maintain and harvest their (mostly rented) fields.

Instead of public institutions, which have been progressively dismantled, they utilize an intricate network of labour intermediaries, called caporali, to recruit this flexible labour force of predominantly immigrant workers. Especially during the time of harvest, when labour demand is at its highest, a single caporale may organize temporary shelter for his workers.

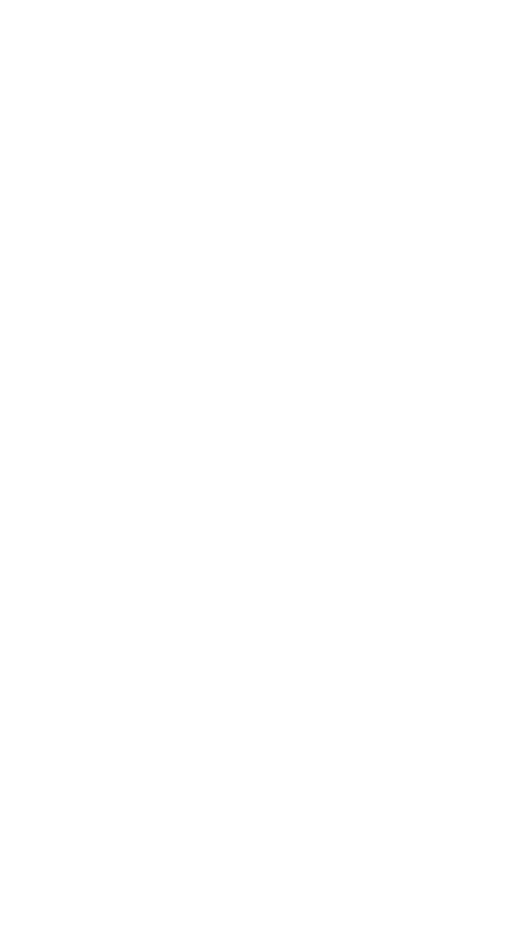

Alternatively, labourers organize themselves autonomously while occupying abandoned ruins in the vicinity of the field. When the work is done, everyone packs their bags, leaving but a few indeterminate traces.

After years of seasonal encampments, traces in the region become more visible. Though sites cannot be formally transfered, these bear the marks of their inhabitants, who subsequently leave strata of rubble on their tracks:

abandoned cutlery, cupboards, clothes, chairs, food, medicines, booklets, lottery tickets, receipts, digitial hardware, music, dvd’s, bottles and cans, bicycles, matrasses, soap, bathing basins, needles and ropes, shoes, bibles and crosses, korans and necklaces, writings on the wall, cellphones, hammers and toolkits, generators, televisions, condoms, and gas canisters.